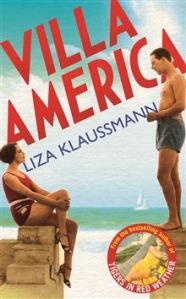

Mumsnet gave me the chance to review Villa America by Liza Klaussmann. I will never turn down a book, ever; but having never read any Liza Klaussmann before (what a mistake!) I didn’t know what I would get from Villa America. What I got was a wonderful surprise. The story of Sara and Gerald Murphy, glamorous 1920 society lynchpins and, as such, hosts to some of the most recognisable names of that era, brought me straight into their world and pinned me there, rapt, unable to put the novel down.

All main characters bar one (pilot Owen Chambers) in the novel are real people. In the case of people like F Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, they are people who I have studied before in the context of the work they produced. It is fascinating therefore to read what might have fleshed out those factual bones; Klaussmann has clearly done a huge amount of research, and therefore the way she writes to fill in the gaps feels perfectly believable, no character’s personification jarring with what we know about them from history, and the dialogue, thoughts and motivations as written by Klaussmann, perfectly believable.

Villa America is a multi-faceted, tremendously colourful tale. We learn about the central characters, Sara and Gerald Murphy, from their earliest lives. Both have characters shaped by unhappy and dysfunctional childhoods; they are childhood friends, not sweethearts, who are reunited after several years and recognise within each other kindred spirits, a shock of realisation that turns into love. They are united in their determination to give each other, and their children, the upbringing that neither of them had. The letters between the two when they first realise that they are destined to be together, and those talking about their first child, Honoria, are realistic and touching.

Their relationship throughout the book and their individual personalities, thoughts and feelings are written sensitively and with great care; as a result, I was able to believe that Gerald could fall passionately in love with someone else while remaining absolutely committed to his marriage and the idyll that he and Sara had created as a result of it. A writer less skilled than Klaussmann would not be able to carry this off, and the careful writing of Sara and Gerald’s relationship is one of the continuously strong and enjoyable threads within the novel.

The reader knows from the very start that the paradise described throughout most of the novel is only temporary. This skillful techique colours reading of the apparently carefree and hedonistic lifestyle at Villa America – as the reader, you know that it is not going to last, unlike the main characters, who for a significant proportion of the novel believe that it will, and viewing it from this position of knowledge gives the story right from the beginning a poignancy that it would not otherwise have. It prevents the characters’ most hedonistic and selfish actions rendering them dislikable, as the reader knows that ‘paradise will be lost’ right from the start. Read from this position of full knowledge, scenes featuring the children and Gerald and Sara’s careful construction of the perfect world for them – even down to Sara’s absolute terror of germs, and the precautions she takes to combat them, which are naive and, ultimately, tragic – are particularly moving. The inexorable movement towards the collapse of the status quo which they have all, to a greater or lesser extent, taken for granted, which we know cannot last, since history tells us so, is also foreshadowed by the excellent writing of Owen Chambers’ experience as a pilot in the First World War, and the vivid description of a fellow aviator’s fiery death. Klaussmann doesn’t shy away from the truth of the 1920s and the horrific events of the war which ushered it in; she writes Chambers’ war experience as believably as the rest of it, and we share in and believe Owen Chambers’ defining life experiences just as we share in and believe the quieter, more personal traumas that have defined the Murphys.

I wasn’t certain how a novel featuring through it a progression of people as well-known as Scott Fitzgerald, John Dos Passos and Ernest Hemingway would work without sounding at least unbelievable and at worst unbelievable and pretentious. We know the Murphys were ‘in real life’ hosts to these people; their relationships are written aside from the work for which they are renowned, and as a result, we believe in the day-to-day lives that Klaussmann writes for them. Zelda Fitzgerald’s depression, her reckless acts as a result of it, and the catastrophic effect of alcohol on her relationship with her husband Scott, but their inability to leave their hedonistic and damaging lifestyle behind were particularly memorable for me.

Villa America pulls the reader into the 1920s and the Murphys’ lives, and doesn’t let you go. When I put the book down, I continued to think about it; finishing it feels like a loss somehow. I would thoroughly recommend it. A proper must-read.

Leave a comment